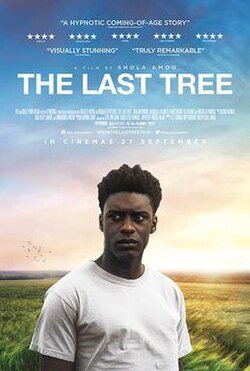

Movie Review for the Week: “The Last Tree” (2019): A Coming-of-Age Story on Identity, Parenting, and the Search for Belonging

Shola Amoo’s The Last Tree (2019) is not just a coming-of-age drama; it is a layered exploration of identity, family, and the fragile pathways young people must navigate in the quest for belonging. Rooted in the director’s semi-autobiographical experience, the film tells the story of Femi, a British-Nigerian boy whose life is shaped by the transitions between foster care, reunification with his birth mother, and the influence of teachers, peers, and community.

The film confronts us with questions central to family life, child safeguarding, and social policy: What does it mean to parent with purpose? How can we guide children through transitions without damaging their sense of self? And what role should society play in ensuring children’s resilience and identity are nurtured?

The Last Tree premiered at the 2019 Sundance Film Festival and was later released in the UK by Picturehouse Entertainment. It is currently available for streaming and rental on platforms such as:

- Amazon Prime Video (rental or purchase in many regions)

- Apple TV / iTunes (rental or purchase)

- Google TV / YouTube Movies (rental or purchase)

- BFI Player (UK audiences)

The Journey of Identity

Femi begins his life in the care of a loving white foster mother in rural Lincolnshire. His childhood there is marked by safety and freedom, though also by a subtle sense of difference. When he is abruptly returned to his Nigerian birth mother in London, the change is not only geographic but cultural, emotional, and psychological.

Suddenly, the boy who had fields to run in is confined to city streets. His once carefree childhood is replaced by loneliness, strict discipline, and the pull of negative peer influences. Femi’s search for identity, British yet Nigerian, rural yet urban, fostered yet biological becomes the heart of the story. In his struggle lies a universal truth: children crave stability, belonging, and affirmation, especially when their environments shift without their consent.

Parenting: Love, Trust, and the Best Interest of the Child

The film paints a nuanced picture of parenting. Mary, the foster mother, gives Femi love and stability but makes promises she cannot keep, deepening his sense of abandonment when those promises break. Yinka, his birth mother, offers structure and cultural grounding but introduces it through rigidity and control, fueling resentment.

What emerges is the reminder that parenting is not defined by biology or mere provision. It is about purposeful nurturing, about combining discipline with empathy, and about listening to the child’s voice. Parents must earn their child’s trust; it cannot be demanded or assumed. Yinka’s evolution in the film from an enforcer to a mother who finally sees her son’s pain, illustrates how even strained parent-child relationships can be redeemed when love is redefined as guidance rather than dominance.

Education as a Lifeline

One of the most powerful interventions in Femi’s life comes not from family but from school. He had a teacher who recognized the boy’s pain, becomes a turning point. Having himself endured similar struggles, he extends compassion and mentorship rather than judgment.

The lesson is clear: educators often hold keys to a child’s resilience. Beyond academics, they serve as stabilizers and mirrors, helping children make sense of their fractured realities. For many young people negotiating family breakdown, migration, or identity crises, a teacher’s understanding can mean the difference between alienation and hope.

Foster Care, Reunification, and the Need for Sensitivity

The film also raises systemic questions about foster care and reunification. While foster systems prioritize reunification with biological parents, The Last Tree shows how abrupt or poorly managed transitions can deepen trauma. Femi’s move from the countryside to London happens with little emotional preparation, leaving him adrift.

Research supports this caution: while reunification can be successful, it requires therapeutic support, gradual adjustment, and prioritization of the child’s emotional best interest. Foster parents must also avoid making binding promises that can later fracture trust. Ultimately, the system must balance administrative timelines with the child’s lived reality.

Key Lessons

For Parents

- Parenting requires empathy, not just discipline.

- Transitions such as reunification or relocation, must be managed with sensitivity.

- Trust is earned, not assumed.

For Educators

- Teachers play a stabilizing role far beyond academics.

- Attention to a child’s unspoken pain can prevent negative pathways.

- Affirming a child’s full identity supports resilience.

For Policymakers and Foster Systems

- Reunification should be gradual and child-centered.

- Support services for families post-reunification are essential.

- Training foster parents on trust-building and boundaries is critical.

For Society

- Identity formation is fragile; stigmatization worsens alienation.

- Safeguarding children is a collective duty, not a private family matter.

- Communities must create inclusive spaces where children belong.

Conclusion

The Last Tree is a deeply human film that holds a mirror to the complexities of parenting, identity, and social responsibility. Femi’s story challenges us to rethink what it means to truly safeguard a child: not merely providing shelter or enforcing discipline, but nurturing trust, guiding through transitions, and affirming identity in all its dimensions.

Ultimately, the film reminds us that the question is not only “What will this child become?” but “How will we, as parents, educators, and society, guide them there without breaking the roots of who they are?”